Garden State of mind: the slippery slope of slackerism for listless young men

I recently re-watched Garden State. Here was a film that had unmoored senior-in-high-school me the first time I’d seen it back on a dreary winter afternoon in early 2007. It must have been a Friday, one of those blessedly free slates to start the weekend I reveled in between the end of cross country season in November and the start of track workouts. Wait. Those started in January. Which is when I remember first watching Garden State.

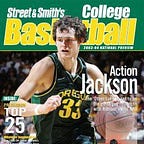

Maybe this was how it happened. I’d gone for a run after school, gallivanting along the nearby trail to the nearby park, thus sating my need for physical exertion through a lung-churning, heart-rate-elevating ten-miler so I could collapse on a couch later and lose myself totally to a screen. A little college basketball. Some Winning Eleven 9. But mostly films.

What I’m trying to prove, of course, in my ham-handed, haphazard way, is that memory is always held hostage by a faulty camera in your mind. (Thank you, Ben Gibbard.) But while it’s hard to pinpoint specifics, the facts and details never quite syncing up, I notice that I do tend to keep pretty good track of the tone. Maybe that’s sufficient.

Here’s what I remember. My first girlfriend had broken up with me over the Christmas holidays, breaking my cherry as far as that that particular marker of young manhood is concerned, and I was about to go on a recruiting visit to Seattle University, where I’d enjoy my first sip of beer.

The Friday of the trip, I received a phone call from said ex-girlfriend, who recounted in choked-up cadence that she’d just been in a car accident. I didn’t understand why she’d called to tell me this; I didn’t know what to say. I must have tried to offer some words of comfort. Seems in keeping with the person I wanted to be at the time.

The weekend after the trip, I’d notice during a school retreat I was roped in to help lead that a cute junior girl was locking eyes with me whenever I glanced in her direction, and in that strange, inexorably magnetic way fate seems to unfurl when you’re young, before the week was out we were hooking up in her friend’s house down the way from a windy hill with a great cross landmark in San Francisco.

There was a particular tone and tenor to the sort of art that moved my teenage self; I vividly remember the imprint of The Shins’ “Phantom Limb” hovering above these afore-mentioned proceedings—the band features prominently in Garden State, of course, but something about Phantom Limb made it the soundtrack to my brief tryst with the junior girl. Maybe it was the sense of an ending.

There was also Death Cab’s Transatlanticism, resplendent in all its overwrought emotion and earnest pursuit of grandiose themes, but there’s also Zero 7’s “In the Waiting Line” during a sped-up scene set at a party in some New Jersey basement toward the start of Garden State. I could relate to that sense of sprawl. Speak, memory of my easily manipulated adolescent self.

Recently I learned a troublesome and tricky tenet of memory from the Danish film You Disappear, based upon the Christian Jungersen book: that each time we access a recollection housed in our balky bank, instead of homing in upon the actual truth we stray farther away from what actually happened. Not an encouraging thought.

The TV show The Affair showed this brilliantly, dividing up episodes so that we perceived them through the eyes of various characters. It hammered home the point that all we have as humans are our reactions to actual events; since we’re always saddled with our own preconceptions, prejudices, and moods-of-the-moment, it follows that we might emerge with an incorrect account of what actually happened.

It’s as if all we achieved by looking back was slapping a fresh coat of paint onto the memory so that it grows increasingly opaque with each subsequent pass. I’m struck by a meditation by Douglas MacArthur, recounted in William Manchester’s biography of the U.S. general: that it doesn’t do to dwell on the past—we hope we’d return to a captivating fire, but what first appears as a comforting glow is inevitably revealed as having long since turned to ashes.

Zach Braff intuited that a certain sort of young man comes to a junction where he goes from always looking forward to always looking back. The Doppler effect pales in comparison to the switch in sound. A guillotine blade doesn’t drop so dramatically. Time, which waxed and waned but always seemed to be at your beck and call, is now totally out of control. Days slip and slide, but they seem to come faster and faster than they ever did before. This is attempting to stop the natural transition to adulthood—it ends with you frozen in time, spinning your wheels.

I wasn’t really enjoying the recent re-entry into Garden State until a scene that perfectly encapsulated a certain sort of ennui shared by a certain sort of young man. It’s Peter Sarsgaard, who’s excellent in his performance as the gravedigger friend with a questionable moral ethic, sitting on a couch in his mom’s house the morning after allowing “Large”, played by Braff, to crash following that afore-mentioned killer party.

After reassuring his friend that he’s fine with being unexceptional, Mark notes that he’s got plenty of time to get his life in order. He’s only 26. The world is in front of him.

It’s impossible to watch the movie and not think of that Ben Affleck speech toward the end of Good Will Hunting, how one day he’ll wake up and he’ll be 50, gasping as he tries to think of where the years went. Time, which had strained like thick stock through a sieve, has long since sped up. It feels like you’re on a conveyer belt hurtling toward death. Each year, the chance that you might be hop off and become exceptional slips a bit further out of reach.

One of Large’s friends is exceptional—at least, he’s done something exceptional. Jesse invented silent velcro—portrayed through a neat flourish by Braff, who notes in a commentary track of the film that it just took a bit of magic in sound design to achieve the desired effect as the invention is showed off—by Mark, no less—later in the film, in front of the fireplace at the mansion Jesse bought with his windfall.

Jesse cashed in on the invention and, as he informs Large, bought a bunch of shit. But when Large asks what he’s doing now, he hems and haws and finally admits, Well, nothing really. He’s got a mansion, but he’s got no furniture to fill it. He hosts parties, he goes to parties, he plays with his toys. The last shot of Jesse finds him drifting in his pool on a sunny afternoon. How very apropos.

That’s the troublesome theme that begins to hit up against you, lapping like water on a pontoon. What is going on with this generation of young men unable to transition into adulthood? Into responsibility. Has it only gotten worse in the fourteen years since I first watched the film?

Maybe that’s why I find the film’s ending so unsettling. Large has just spent a day drifting and dreaming throughout Jersey with Mark and soon-to-be girlfriend Sam, the kind of day tinged with a sort of endlessness endemic to youth.

And that’s the strange thing about it — it’s like Carrie Brownstein and Fred Armisen raving to each other in the Portlandia intro that they’ve discovered, in the Rose City, the manifestation of what life was all about in the ’90s for Gen-Xers rambling through their twenties. They could do the minimum amount of work and just live, baby. They could spend most of their time contentedly drifting.

Eventually the trio stumbles upon a young family watching over a geological wonder. The husband deals in trinket trading on the side, but what’s most striking is the sense of contentment they exude. It’s well-earned. The couple has a baby, they’re moving forward in life. It makes an impression upon Large.

Soon thereafter we get Large’s grand climactic awakening. He finally confronts his father, confronts his past, and confronts his feelings. He gets the girl! And then the film ends with him asking her, “Now what?”

It smacks of The Graduate, for good reason. Much like the drifting Dustin Hoffman before him, Large is the narcissistic sort of modern young man who spent his youth drifting. Eventually he makes a big decision. But is he ready for the consequences?

What remains is the lingering shot of Hoffman and Katharine Ross on the bus after they’ve sprung loose from her marital proceedings to another man. We see their jubilant faces begin to falter as a silent question looms large on the horizon: Now what?

One worries that while reveling in the dramatic event, they’ve forgotten an important tenet of life. After the great event comes the next morning. And the next, and the next, and the next. The drudgery of routine and mundanity. That’s life, and one worries that the likes of Large and co., like so many of their contemporaries in Gen-X, Millennialhood, and beyond, are thoroughly unsuited to fulfill it.

There’s a beauty in accepting entry into the coursing river of time and becoming simply another young family like the many that came before you. Learning to put others’ needs before your own. To find comfort in that mundanity.

There’s meaning in it too, and in an age where more and more young men are drifting along, it needs to be heeded.